24. Speedway’s Beginnings Led to Greater Things

James Glass

Column that appeared in the Indianapolis Star onOn this 100th anniversary of the Indianapolis 500, it is interesting to recall its beginnings and how race became one of world’s greatest sporting events.

It began, of course, with Carl Fisher, who dreamed of a race track that would allow the engines, bodies, and tires of the still-new automobile to be tested at speeds and distances that were impossible on existing dirt roads or city streets. Fisher and his long-time friend and business partner James Allison had already made a fortune transforming into reality another of Fisher’s brainstorms—the Prest-O-Lite Company, makers of the first practical headlights for cars. With the help of Allison’s business acumen and organizational ability, the 2 ½ mile oval track took shape northwest of Indianapolis on West 16th Street. Fisher persuaded two other Indianapolis businessmen to provide financial backing—Arthur C. Newby, another close friend and principal in the National Motor Car Company, and Frank Wheeler, head of the first concern to produce carburetors for gasoline engines. In the first Speedway races in 1909, the initial macadam surface melted and created dangerous ruts in the track surface, causing multiple deaths. Risking their fortunes, Fisher and his partners then spent an additional $200,000 to create the most durable road surface then known—3 ½ million vitrified paving bricks laid on a concrete base with special, high-quality construction techniques and a design intended to foster stability and adequate banking on curves.

Fisher, a natural promoter, believed that holding a single race in 1911, with a length exceeding any previously attempted and a handsome $35,000 total purse, would draw the best racing drivers and large crowds to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. There were other raceways in major cities of the country, but many were constructed with board surfaces and had shorter courses. Fisher portrayed the 1911 event, with the brick track and 500-mile length, as the “greatest automobile race” anywhere. And the response from the 80,000 people who attended the first 500, the American and European automobile manufacturers who entered cars, and the 40 top drivers who participated bore out Fisher’s optimism.

Ray Harroun, a racer and engineer for the Marmon automobile company of Indianapolis, helped to design a 6-cylinder racer for his firm that won the first 500. Harroun later said it was the most grueling experience of his life, as he struggled with unresponsive steering to keep his car on the track. He also complained that the ignition on the Marmon Wasp was so inadequate that he was unable to coax the vehicle to more than 100 miles per hour on the straight-of-way. The tires at the 1911 race were all fabric and would blow out so frequently that some drivers had to stop fifteen times to change them. Harroun’s experience illustrated the value of the 500 for manufacturers and ultimately the driving public. The failings of automobile design could be demonstrated on a punishing, lengthy course and corrected for later use in regular passenger cars. Indianapolis-made engines and bodies dominated in the race’s first two decades. Joe Dawson won with a National car made by Arthur Newby’s firm in 1912, and Stutz cars made in the state capital were raced in 1911 and won a tenth-place finish in 1914 for Eddie Rickenbacker, later owner of the Speedway. In the 1920s, Duesenberg engines helped four drivers win the race, designed by Fred Duesenberg and made by the Duesenberg Motor Company of Indianapolis.

The 500 Mile Race by the 1920s was attracting over 100,000 people and was indeed the top automotive sporting event in the world. It had also become the chief testing ground for improvements for the auto industry worldwide. Carl Fisher’s vision was vindicated.

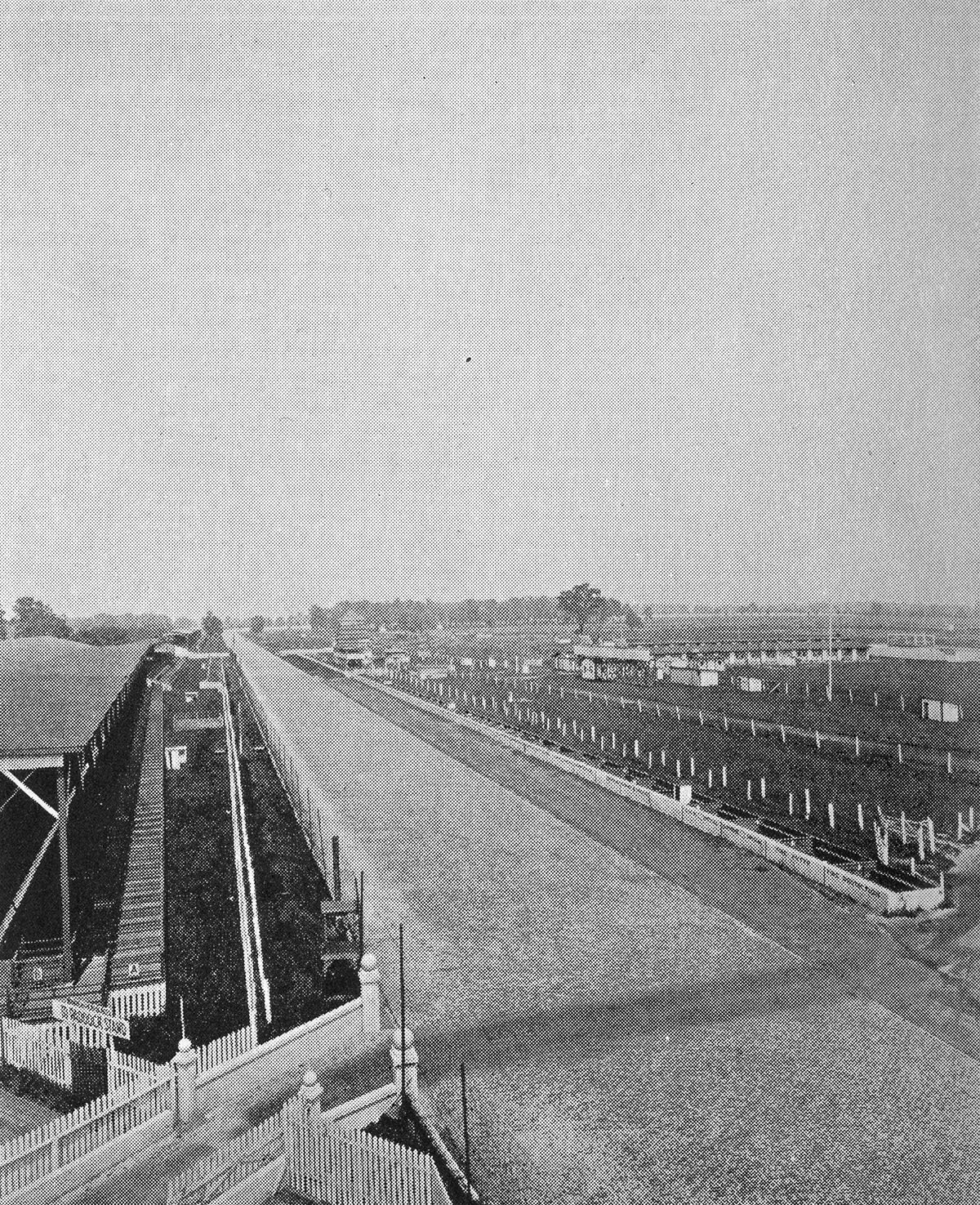

Speedway track in early 1920s. Souvenir of Indianapolis, Kingan & Co.