Indianapolis belongs to a select group of state capitals–it was created to serve as the capital of its state, and it was given a distinctive plan designed to help a fledgling settlement grow into a city with impressive civic spaces, vistas, institutions, and transportation circulation.

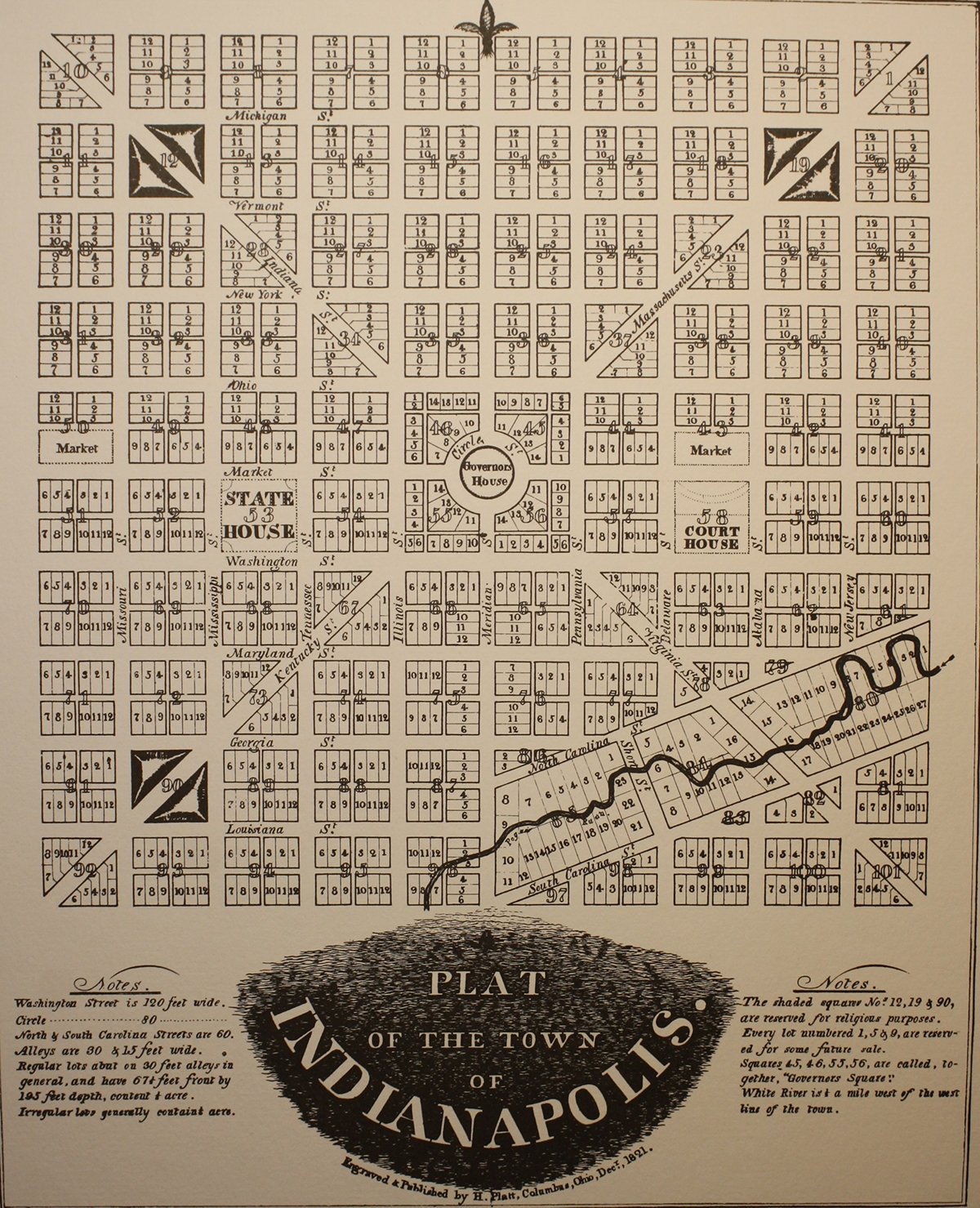

The Indianapolis plan was largely the vision of Alexander Ralston, a Scottish immigrant who had worked as a surveyor laying out the plan for Washington D.C. in the 1790s. Ralston drew on his experience in Washington when he designed the Mile Square plan of Indianapolis in 1821. From the national capital, he borrowed the idea of a circle and diagonal avenues imposed on a gridiron (checkerboard) pattern of streets. The Circle Ralston saw as the central civic place of the capital. The four diagonal avenues he laid out to create grand, 90-foot wide vistas and facilitate transportation to and from the center. The rest of the Mile Square streets, laid out in the gridiron pattern, offered easy access by foot, wagon, or carriage from one point in the plan to another. Ralston followed the tradition of the Washington plan and other new state capitals and reserved sites in the Indianapolis plan for civic buildings and public functions, including a state house square, county courthouse square, and two half squares for city markets. He also had his eye on the commercial future of Indianapolis and gave Washington Street--the east-west street just south of the Circle--a 120-foot width, in anticipation of it connecting with the National Road–the great east-west pioneer road being built by the federal government.

To what extent has Ralston’s vision been realized? The Circle has been an unqualified success. From an early point, it has served as the principal civic gathering place and symbolic center of the city. The Indiana Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument, constructed some 70 years after Ralston, has projected an element of monumental grandeur that has made the Circle a magnet for people and public events. So, too, the squares Ralston reserved for the state house, court house, and markets have been successful. The majestic current State House sits on two squares, rather than one, but is sited to dominate its section of the plan. The courthouse square has held two court houses and now holds the City-County Building, the center of city and county government. The eastern market square still contains the Indianapolis City Market, which has sold farm produce for most of its 175-year history. Washington Street did indeed become the route of the National Road (later US 40) through Indianapolis and over 180 years, hundreds of retailers and wholesale businesses have been attracted to it.

In other respects, the community has not always appreciated Ralston’s vision of a metropolitan capital. The diagonal avenues have been perhaps understood the least. Far from allowing them to function as grand boulevards offering long vistas in and out of the downtown, governmental and private planners since World War II have advocated closing or building over some of each avenue in the Mile Square. Only one, unused block survives of Kentucky Avenue, the southwest diagonal, which was vacated in the 1960s and the 1970s to create superblocks for construction of the Indianapolis convention center and for the Hyatt Regency Hotel. On Massachusetts and Indiana Avenues, during the 1960s and early 1980s, the first blocks of both were vacated to create building sites for the Indiana National Bank Tower (now One Indiana Square) and the American United Life Building. More recently, a central block of Virginia Avenue, the southeast diagonal, although still open to traffic, has been covered over by the massive parking structure for Conseco Field House. Massachusetts Avenue shows best the promise offered by the diagonals. Since the 1970s, it has become a center for art galleries, restaurants, and music venues and provided the boulevard-like vista that Ralston intended. The gridiron pattern of the original plan has also suffered closures, as parts of streets in the south and western sections of downtown have been closed. That has facilitated assembly of development parcels and decreased crossings over the downtown canal, but interrupted the smooth flow of traffic that Ralston’s plan anticipated.

What can we do to follow what remains of Ralston’s vision? We can develop more public awareness of the capacity of the original plan to make the capital city impressive. Design alternatives to modifying the plan can be explored in order to achieve development objectives. And we can use the thriving east side of downtown, where the plan has been altered the least, as a model for the rest of the Mile Square.

Ralston’s Plat for the Mile Square Plan of Indianapolis, 1821